Headphones, Railroads, and ref Statements: the chaotic world of model dependencies

Imagine that the year is 2015, and most people are still using wired headphones. You reach into your bag and pull out a horrendously tangled pair. The immediate reaction of annoyance turns to an almost therapeutic feeling as you make progress, and finally a tiny feeling of accomplishment as buds and wires are set free.

Now imagine that for some reason you’ve offered to store several of your colleagues’ headphones in your pocket alongside your own. This time, the untangling process is a bit more difficult, and just as you’re making progress toward separating yours from the rest, a new pair of headphones is added to the bundle, and then another one…

This is kind of what it feels like to maintain an analytics engineering project. Of course, most contributors to analytics projects aren’t doing so with an intent to inject new complexity for others to deal with, the effect is common, at times frustrating, solvable at best 1, and mitigatable at worst.

Dependencies in dbt: both an asset and a liability

The dominant tool for facilitating analytics-ready datasets is dbt, which popularized a modular design framework. The tool enables analytics engineers to create reusable building blocks that can be combined with other building blocks in a defined sequence to produce a canonical dataset, using SQL. This defined sequence is the focus of this post, and is defined by a Directed Acyclic Graph – a DAG, for short.

This way of working has been a godsend to people like me, but isn’t without its frustrations. For example, when dbt projects grow in complexity2, it can be difficult to add new features without (1) impacting existing features or (2) constricting flexibility in the future.

The former is relatively straightforward, as developers running the DAG locally have a tight feedback loop to uncover breaking changes. The latter, flexibility implications of newly added features, usually goes undetected until a developer finds themself faced with an undesirable design tradeoff.

Designing a public transit system

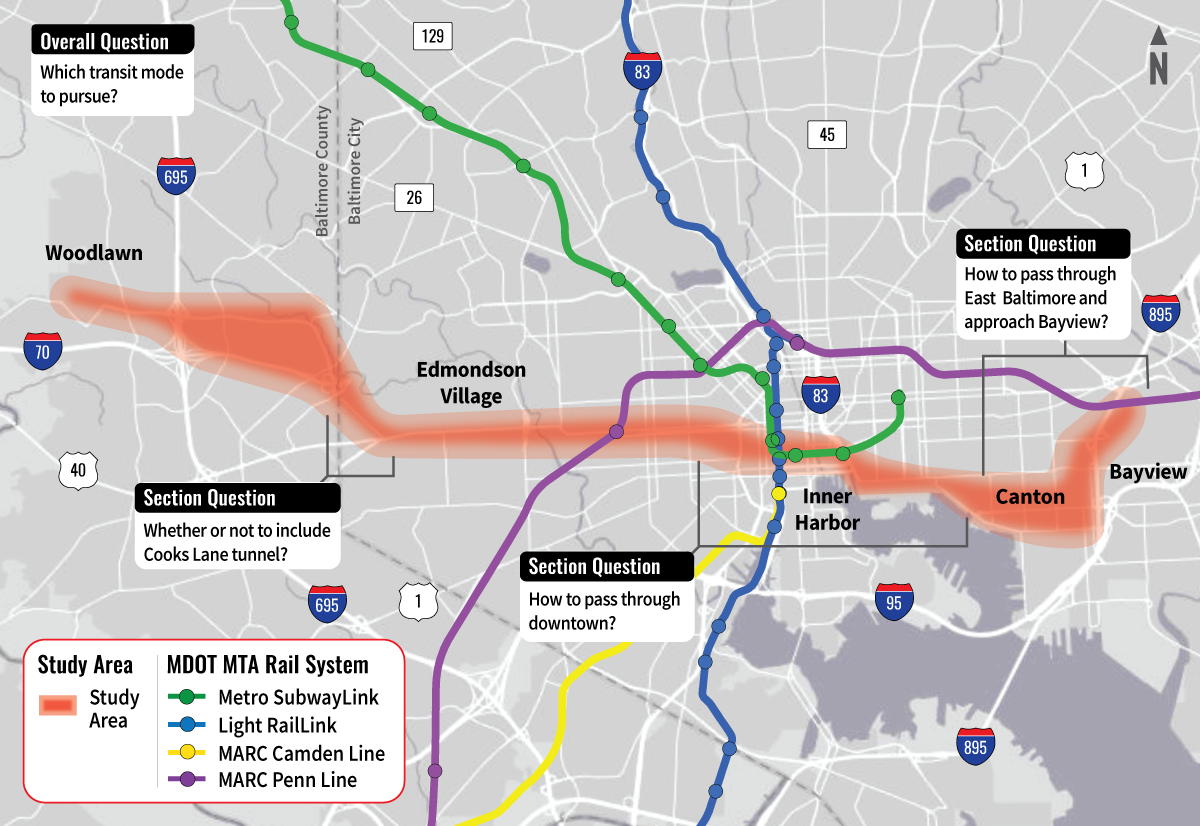

The design decisions that go into building analytics infrastructure are similar to how I envision the development of a new train system. In Baltimore, MD, where I live, there has been a 20-years-long debate over the route and mode of transit for the construction of “The Red Line,” which will connect the east and west parts of the city. The planners have released a handful of maps, which illustrate the potential path, as well as several critical questions:

- Should the mode of transit be heavy rail, light rail, or a rapid transit bus line?

- How should the system pass through the populous downtown area?

- Where, exactly, should the tracks even be built?

Each of these questions has clear tradeoffs: cost of construction, projected ridership, housing to be eminent domained and demolished, and environmental impacts.

These questions aren’t unlike those that a developer should ask when adding new models or features to a dbt project:

- How compute-intensive is the new feature?

- How does the new feature impact existing models and features within the project?

- Where should the new model or feature be positioned in the context of the project’s DAG to maximize throughput?

The obvious counterpoint to this is that software development costs are marginal relative to the construction of a train system, which requires years and potentially billions of dollars to build, and with no real option to refactor it later.

My experience has been that this is mostly true: it is often feasible and sometimes fun to refactor a DAG to unlock warehouse computing throughput and modeling flexibility, but it’s rarely feasible or fun to get executives to prioritize this type of work over net-new or novel feature development.

Making the tangledness more predictable

The irony isn’t lost on me that the analytics engineering job function, whose mission it is to create trusted sources of measurement and analysis, is often unable to measure the impacts of the things it builds on the things it’s previously built.

For the past couple years, I’ve fantasized about developing datasets and metrics that make it easier to measure not only how valuable the things we build are, but how they affect other things we’ve built – moneyball for analytic warehouses. If we could price the ongoing maintenance costs of a model, we could make design decisions3 in an objective way.

There are a growing number of tools and resources that make this vision possible. Three examples come to mind:

- Abstract Syntax Tree (AST)-based solutions like SQLGlot translate SQL into machine-readable syntax, which enables true column-level lineage.

- SELECT’s monitoring packages, which query against Snowflake’s account usage datasets to summarize costs per query, warehouse usage, and more.

- Snowflake’s programmatic access to its Query Profile

I imagine combining these into datasets that provide answers to the following questions, both to identify areas of an existing project that are most taxing from a cost and maintainability standpoint, but more importantly, how taxing a prospective change is expected to be before it’s productionalized. These questions are not-so-unlike those posed by the Red Line Planners in the map above!

- Are there indicators of suboptimal query design (unnecessary table scans, cartesian joins)?

- What are the maintenance costs of a new model from, given its dependencies?

- How far downstream or “right” in the dbt project a model sits, and which dependencies are most responsible (i.e., a shift-leftedness score metric, a 0-100 scale where a low score describes a model that runs early in the DAG, and a high score represents one that runs at the very end).

- Which critical downstream datasets does a given model serve? And how (i.e., which columns)?

- How do we know which downstream datasets are most critical (i.e., how many people are using them, and in which contexts)

As the classic idiom goes:

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. And if you’re gonna join ‘em, you should have visibility into the implications of that join to the model itself, its dependencies, its descendants, and the overall maintenance burden it adds.